Unreliable Boyfriends

Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan once confessed “Since I’ve become a central banker, I’ve learned to mumble with great incoherence. (…) If I seem unduly clear to you, you must have misunderstood what I said.”1 Clear communication and forward guidance have since become key elements of the monetary policy toolkit. Yet, Central Banks still quite often reverse policies or abruptly shift the tone of communication with the market. Just a couple of weeks ago, Bank of England (BoE) Governor Andrew Bailey was asked if the Bank (implicitly, he) had become unreliable boyfriend number two,2 after BoE failed to deliver a rate hike that was considered a done deal by most market participants.

These policy U-turns render global rates and exchange rate investing an exercise of deciding when to trust policymakers and when to be skeptical. Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech in 2012 delivered credible, time-consistent guidance. Currently, there are important policy tradeoffs that may prompt Central Banks to change course, despite previously well telegraphed plans. This means more volatility and, in some countries (though not all) a higher risk of policy accommodation removal sooner than originally signaled by monetary authorities.

Commitment Problems

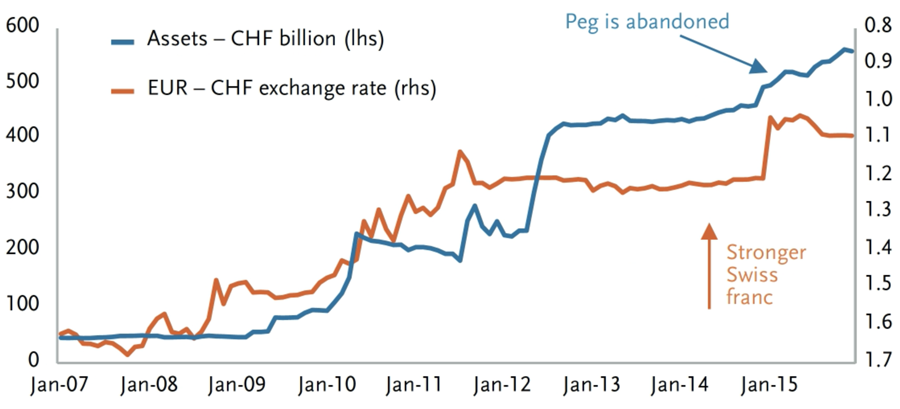

Flip flops in Central Bank communication and policy are not a new problem. Take, for example, the decision by Swiss National Bank (SNB) to abandon its exchange rate policy in 2015. Since 2011, SNB had been intervening in the market to maintain a minimum exchange rate of Swiss franc 1.20 per euro, therefore preventing excessive appreciation of the Swiss franc. During the December 11, 2014 policy meeting, SNB stated that the bank would continue to implement its exchange rate policy “with the utmost determination, given that “deflation risks have increased once again and the Swiss franc is still high.” One month later, SNB abandoned the exchange rate peg and let the Swiss franc float freely: the currency immediately appreciated close to 20% against the euro.

Swiss National Bank Foreign Assets and Euro-Swiss Franc Exchange Rate

Source: Bloomberg

Why did SNB unexpectedly give up its currency peg? Most likely due to limits to balance sheet expansion. The Swiss franc was the target of a different kind of speculative attack, one in which market participants continued to sell euros, buying Swiss francs in expectation that SNB would not keep accumulating foreign currency-denominated assets at that pace and would eventually let the currency appreciate. The bank risked larger and larger capital losses in its euro-denominated assets, if the transition to a free float was delayed but ultimately inevitable.

Looking beyond SNB experience with the exchange rate peg, there are three factors that can create a wedge between initially stated Central Bank intentions and the actual policy path that is delivered:

- Forecast-based forward guidance

- Limits to balance sheet expansion

- Political economy factors

Forecast-based Forward Guidance

State contingent forward guidance – which depends on economic forecasts – is vulnerable to forecasting errors and subsequent need to adjust policies and communication. This is not due to a shortage of insightful and well-trained economists at Central Banks’ research departments. It is just that forecasting output and inflation is quite hard, particularly when there are underlying structural changes that economic models are not capturing.

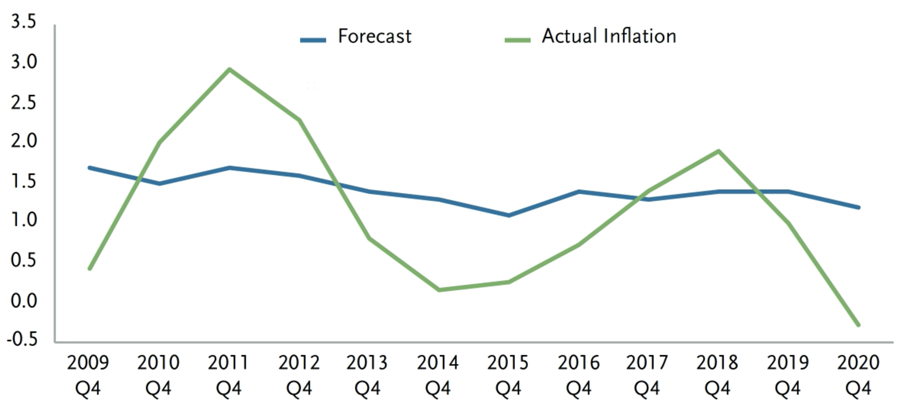

Take, for example, the ten year period after the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, and that included the 2012 European debt crisis. During this period, the European Central Bank (ECB) forecasts missed the actual one year ahead print by a sizable margin. Most importantly, it systematically overestimated inflation during that decade, with median forecast error of +0.5%.

ECB – 1 Year Ahead Inflation Forecast (%)

Source: Bloomberg

ECB President Christine Lagarde recently made use of state contingent forward guidance during the October 28 policy meeting press conference. When asked if markets were making a mistake by pricing a rate hike by the end of 2022, Madame Lagarde argued that ECB forecasts did not envision inflation sustainably at 2% level that early in the current cycle. Markets took that answer as a half-hearted defense of ECB forward guidance, and eurozone rates sold off accordingly.

During that same week, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) de facto abandoned its yield curve control (YCC) framework, not intervening to maintain the yield target of 0.1% for the 3 year maturity Australian Government bond, even after the bond yield soared past 0.7%. It was only on November 2, during the scheduled monetary policy meeting, that RBA acknowledged that the YCC policy was officially discontinued. Explaining the decision, RBA clarified: “At the time the yield target was introduced, the Board assigned a very low probability to an increase in the cash rate over the three-year horizon of the target. (…) Today, more than a year and a half on, the balance of probabilities is a little different.”

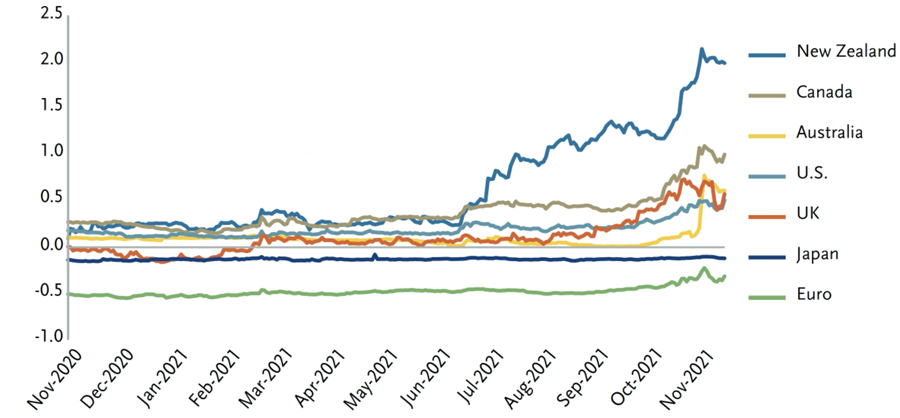

2 Year Government Bond Yields (%)

Source: Bloomberg

Bank of Canada (BoC) also surprised markets recently, ending balance sheet expansion months before it was expected to do so, and signaling that rate hikes could take place sooner than previously guided. Once again, forecast-based forward guidance played a role in front end rates selloff that took place after the October 27, 2021 BoC meeting. BoC had previously indicated that a precondition for rates liftoff was the closing of the output gap (a measure of slack in the economy) and that it did not expect such condition to be met before the second half of 2022. On October 27, 2021, the bank brought forward the timing of the closure of the output gap by two quarters, triggering a bear flattening of the Canadian curve.

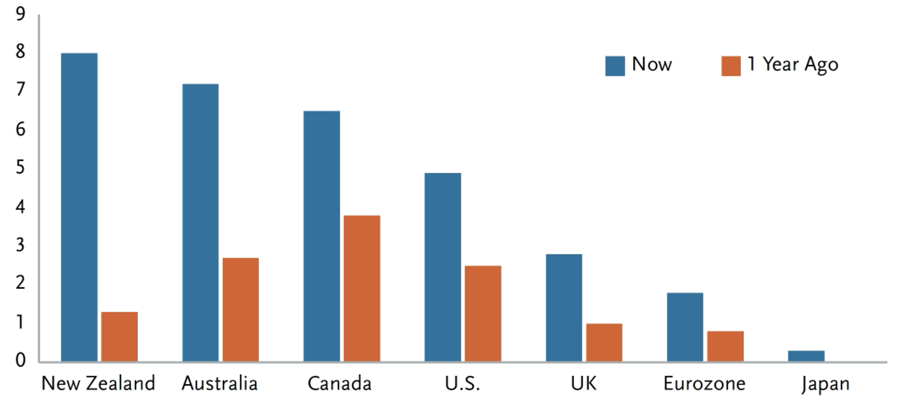

Number of 25 Basis Points (bps) Hikes Priced, 5 Year Horizon

Current vs. 1 Year Ago

Source: Bloomberg; data as of 11/10/2021

Limits to Expanding Central Bank Balance Sheet

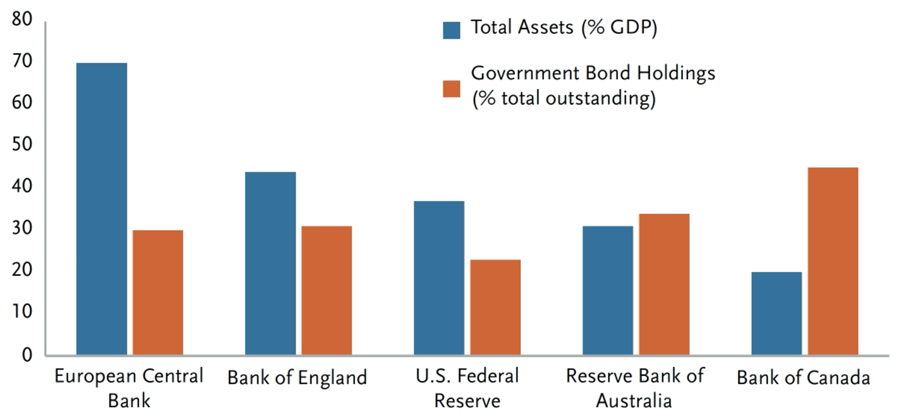

The rising size of Central Bank holdings of government securities (as a percent of total outstanding) can quickly undermine the sustainability of open-ended quantitative easing and yield control policies. This is especially true in the case of a small open economy such as New Zealand, and an important factor that explains why the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) ended its asset purchases early and rather abruptly last July.

By the time the decision to end QE was made, RNBZ already owned close to 50% of government bonds outstanding. Bank of Canada’s decision to end balance sheet expansion several months earlier than the market expected can also be interpreted in light of the already sizable ownership of government bonds (45% of total).

While the U.S. Federal Reserve and the ECB may face less binding restrictions, given the size of their economies and bond markets, the problem is obviously relevant for smaller open economies. According to Bloomberg data, the last time RBA purchased ACGB 04/2024 in order to defend the 0.1% yield target was just a few days before the target was abandoned. The bank bought AUD 1bn worth of the security, taking its ownership to 64% of the total outstanding of that specific bond.

Central Banks Balance Sheet

Source: BAML

Public Economy Factors

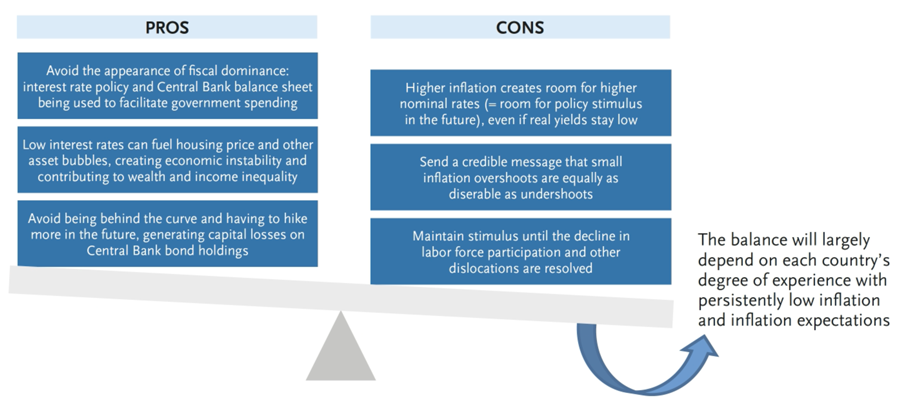

Pre-pandemic, policymakers in several advanced economies were quite concerned about a systematic undershooting of the inflation objective. It prompted the U.S. Federal Reserve to adopt a new policy framework – the flexible average inflation targeting or FAIT – and it encouraged the ECB to also modify its target from “just below 2%” to a symmetric target around 2%. Small conceptual differences apart, the two frameworks require that inflation overshoots above 2% be tolerated for some time, in order to ensure that inflation and inflation expectations are, on average, at 2%.

After several months of elevated inflation prints worldwide, we are starting to see signals that the actual implementation of average inflation targeting – to the extent that it may require slow policy normalization and tolerating higher levels of inflation – could be challenging. One reason is that, while the median voter may not draw a direct link between low inflation and her personal finances, she might more easily draw a negative link between 3 or 4% (or higher) inflation and her purchasing power. Bank of Canada implicitly acknowledged this problem in its most recent policy meeting statement:

“We know higher prices are challenging for Canadians, making it harder for them to cover their bills. I want to assure you that inflation is not going to stay as high as it is today, even if it is going to take somewhat longer to come down. The Bank of Canada is committed to ensuring that price increases don’t become ongoing inflation.”

In addition to the issue of public aversion to inflation, there are other factors, also of political economy nature, that could eventually prompt select Central Banks to remove policy accommodation faster than in the previous cycle. Central Bank independence and avoiding even the appearance that monetary policy is subordinated to fiscal needs is one of them. Avoiding asset price bubbles and housing market speculation (which can deepen wealth inequality) is another one. The addition of sustainable housing prices to RBNZ operational goals is a prescient reminder of the multifaceted set of goals and trade-offs that Central Banks will continue to face:

Conclusions

Given that policy miscommunication and flip flops are a frequent occurrence, we find it helpful to take a step back from noisy day-to-day policy statements (and what markets make of it), and think about the big picture. This broader perspective tells us that we could see a global policy normalization cycle that is not synchronized and one in which differences in inflation patterns will play a much more important role compared to the drivers of policy normalization after the 2008 financial crisis:

- Countries that were less exposed to the problem of persistently low inflation and low inflation expectations will likely choose to move away from the zero lower bound, take advantage of current elevated inflation and closing output gaps to implement a few rate hikes, sooner rather than later. The decision will be supported by concerns related to excessive housing price appreciation. Canada, New Zealand and Norway fit this profile (RBNZ has already implemented one rate hike). The reasons Central Banks in these countries have to be more hawkish seem to be already fully priced. In fact, the pace of rate hikes that the market is currently pricing over the next two years seems a bit excessive, particularly in Canada and New Zealand.

- Eurozone and Japan will likely fall on the opposite end of the spectrum and remain committed to exceptionally gradual policy accommodation removal, given their longer history with stubbornly low inflation. Critics will still point to loss of Central Bank independence and fiscal dominance issues. However, not letting inflation rise sustainably to higher levels before tightening policy could leave the two regions stuck with old problems or even make them worse – and be reminiscent of the ECB unwise rate hike in 2008.

- The U.S., UK and Australia fall in the middle of this spectrum. Pre-pandemic, inflation in the UK was not exactly low, but the UK economy has seen the largest productivity and potential output decline among advanced economies during the last decade. Downside economic activity risks driven by Brexit still linger. The US and Australian economies have displayed healthier growth dynamics but inflation has been persistently below target. The Fed has set reaching maximum employment as one of the requirements for a rates lift off (which in turn will require at least some improvement in labor force participation). Over the next twelve months, the Fed and BoE will have a great incentive to implement one or two rate hikes, move away from lower bound, then make the pace of further tightening contingent on the outlook. In Australia, RBA will have to make further progress marking to market its economic forecasts and signaling that a rate hike may end up taking place sooner than originally telegraphed.

1 “How the Fed Learned to Talk,” New York Times opinion, Douglas R. Holmes, February 1, 2014.

2 “Unreliable boyfriend” number one was likely former BoE governor Mark Carney. In 2014, Pat McFadden, Labour MP, complained: “We’ve had a signal that rates probably wouldn’t rise until 2016, we then had a market expectation that rates would go up in 2015, we then got a speech saying that might be an underestimation. It strikes me the Bank is behaving a bit like an unreliable boyfriend. One day hot, one day cold, and the people on the other side of the message are left not knowing where they stand.”

Disclosure

This material is for general information purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security. TCW, its officers, directors, employees or clients may have positions in securities or investments mentioned in this publication, which positions may change at any time, without notice. While the information and statistical data contained herein are based on sources believed to be reliable, we do not represent that it is accurate and should not be relied on as such or be the basis for an investment decision. The information contained herein may include preliminary information and/or "forward-looking statements." Due to numerous factors, actual events may differ substantially from those presented. TCW assumes no duty to update any forward-looking statements or opinions in this document. Any opinions expressed herein are current only as of the time made and are subject to change without notice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. © 2024 TCW